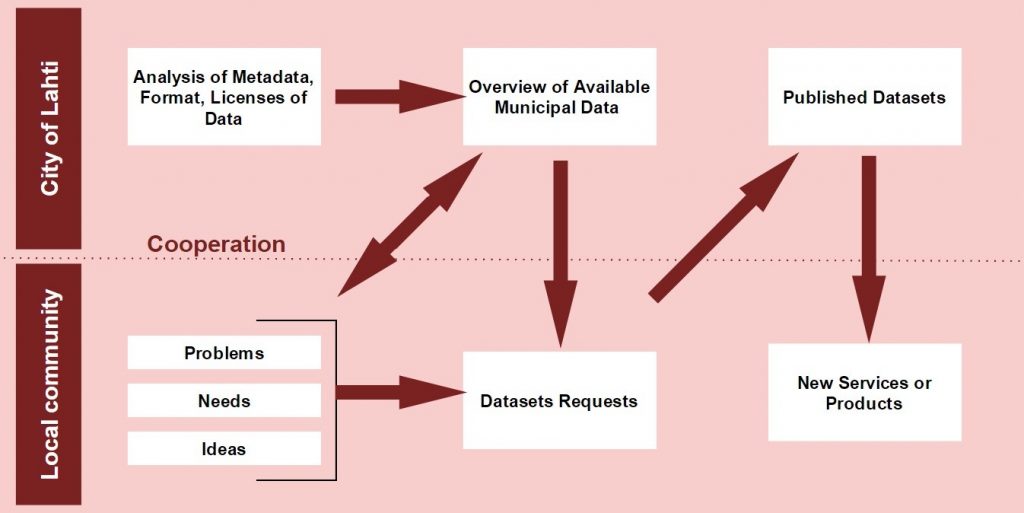

An aim of cooperation between Ho (Ghana), Rustenburg (South Africa) and Lahti (Finland) is identifying circular economy opportunities and pilot projects. The co-creation process includes baseline studies, stakeholder discussions and workshops. The article presents two identified waste pilot projects in Ho.

Author: Maarit Virtanen

Introduction

In Ho, the lack of waste management services is visible and there is no organised recycling of materials except for metals and small amounts of plastics. However, for example, organic waste is widely used for animal fodder. There is also reuse for items like empty plastic bottles, containers and cardboard boxes. Furthermore, various reuse, renting and repair services are available around the town. Even the public transportation is based on an efficient taxi system with cheap prizes, joint rides and constant availability of service.

Ho Market Place Waste Recycling

The new Ho Market Place is expected to open in 2017. The Market Place hosts around 2000 sellers on market days, which take place every fifth day. The market place is used daily and has been identified as a suitable place to pilot waste sorting and recycling. The new main market building has space for 390 sellers, and there are also several other new stalls in the area. Almost everything is sold in the market; garden and agricultural products, a lot of yam and charcoal, fish, groceries, textiles, clothes, plastics, pesticides, canned food etc.

Figure 1. Ho Market Place

The largest waste fractions generated at the Market Place are plastics, cardboard, paper, organic waste and charcoal waste. Almost all waste fractions generated have some kind of monetary value, although currently only metals, plastics, paper and cardboard have a possible buyer in Ho. Materials are transported to Accra for processing.

For the piloting of recycling, it was decided to focus on the biggest waste streams that already have a market, and to organic waste. A composting facility is needed for organic waste recycling. The stakeholders involved in the value chain include waste producers, waste management companies, private companies buying and processing recyclables, the Ho Municipal Assembly, Market and Traders Associations, research institutes, farmers and other possible users for the compost, and local NGOs.

The separation of recyclable waste at market place can be done by waste pickers or buy sellers. Since waste separation is a totally new concept for the sellers, and they change, education can be challenging. The best solution could be to have separate waste bins for organic waste and other recyclables, and also have trained waste pickers circulating the area and collecting materials. At the moment, collecting recyclable waste is not seen a worthwhile job, so awareness raising is also needed on the value of materials.

Before starting the pilot, the amounts and availability of waste must be studied. There is already local utilisation for, for example, some of the organic waste and a token fee can be expected for it. What is also needed for the pilot is intensive training for waste pickers and market sellers, and equipment for waste collection. In addition, municipal waste regulations should be formulated to support waste sorting and recycling. A separate plan is needed for the small-scale composting facility.

Figure 2. Waste ends up in streams and rivers in Ho

Waste Recycling Pilot at Ho Technical University

Ho Technical University (HTU) has about 5 000 students and a campus area with several departments, offices, restaurants and student hostels. HTU has proposed a waste recycling pilot in the campus. The largest waste fractions produced at HTU include paper, cardboard, plastics and organic waste. There is also some metal and cans. In addition, small amounts of e-waste, glass, leather waste, and used clothes are produced. The waste is generated by students, staff, vendors, restaurants, workshops and hospitalities. Organic waste includes garden waste.

Similar to the market place, the easiest waste fractions to start with are those with existing markets, like cardboard, paper and plastics. Considerable amounts of paper are stored at campus, so the first step in the pilot is to organise their recycling. The collection of organic waste requires a composting facility, which should be a common one for campus and organic waste from the market. The university has a Department of Agriculture that has a farm and could participate in composting and relater research.

Since waste recycling is new in Ho, HTU campus would provide a good piloting opportunity for also testing different communication and education methods with students involved in the whole process. In addition to material recycling, different upcycling and reuse opportunities can be explored together with students.

Next Steps

The circular economy concept has been recognised with enthusiasm in Ho, and a wide range of stakeholders has been involved in the two workshops organised. The next aim is to co-create concrete pilots to test the concepts. Cooperation with Ho is a part of Co-creating Sustainable Cities project funded by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, and coordinated by Lahti University of Applied Sciences.

Author

Maarit Virtanen is the Project Manager for Co-creating Sustainable Cities and Kiertoliike projects at Lahti University of Applied Sciences.

All photos by Maarit Virtanen.

Published 28.11.2017

Reference to this publication

Virtanen, M. 2017. Circular Economy Co-creation in Ho, Ghana. LAMK Pro. [Electronic magazine]. [Cited and date of citation]. Available at: http://www.lamkpub.fi/2017/11/28/circular-economy-co-creation-in-ho-ghana/