Tämän artikkelin tarkoituksena on kuvata opiskelijoiden kokemuksia verkossa toteutetun Learning Cafe -menetelmän toimivuudesta. Oppimistehtävä toteutettiin osana Lahden ammattikorkeakoulun tarjoamaa kesäopintojaksoa Digitaaliset palvelut arjen apuna. Aineisto kerättiin kyselylomakkeella opintojaksolle osallistuneilta opiskelijoilta. Opiskelijat kokivat Learning Cafe -toteutuksen teknisesti toimivaksi ja ohjeet riittäviksi. Lisäksi heidän kokemuksensa oppimismenetelmästä olivat positiiviset ja he ovat valmiita suosittelemaan Learning Cafe -toteutusta myös muille opintojaksoille. Tutkimuksen tulokset kannustavat verkko-opintojaksoja toteuttavia lisäämään toteutuksilleen yhteistoiminnallisia menetelmiä.

Kirjoittajat: Hannele Tiittanen ja Sariseelia Sore

Johdanto

Digitalisaatio vaikuttaa vahvasti kaikkeen toimintaan, myös koulutusalalla. Lahden ammattikorkeakoulussa on runsaasti kysyntää paikasta riippumattomille opinnoille ja verkko-opintojaksoja toteutetaan enenevässä määrin. Erityisesti monipuoliset verkkototeutukset motivoivat oppijoita (Chang & Kang 2016) ja opiskelijat ovat kokeneet reaaliaikaisen verkossa työskentelyn vastaavan laadultaan kasvokkain tapahtuvaa luokkaopetusta (Ward ym. 2010). MacNeill ym. (2014) painottavat, että yhteistoiminnallisen työskentelyn tavat ovat oppimisen näkökulmasta tehokkaampia kuin yksilötyöskentelyyn perustuvat työskentelymenetelmät, myös verkkoympäristössä. Näin ollen on tärkeää pyrkiä rakentamaan myös verkko-opintoihin yhteistä tiedonrakentamista tukevaa toimintaa.

Learning Cafe on paljon käytetty ryhmätyöskentelymenetelmä, jonka tarkoituksena on yhteisen keskustelun avulla rakentaa uutta tietoa ja yhteistä ymmärrystä tarkasteltavaan aiheeseen. Luodaksemme yhteistoiminnallisia oppimiskokemuksia verkko-opinnoissa, toteutimme verkko-opintojaksollamme digitaalisen Learning Cafen. Tämän tutkimuksen tavoitteena on selvittää opiskelijoiden kokemuksia menetelmän soveltuvuudesta verkko-opintojaksolla ja siten luoda uutta tietoa digitaalisen yhteistoimintamenetelmän käytöstä verkko-opinnoissa.

Learning Cafe oppimismenetelmänä

Learning Cafe on työskentelymenetelmä, jonka tarkoituksena on ryhmän yhteisen keskustelun avulla rakentaa uutta tietoa ja yhteistä ymmärrystä tarkasteltavaan aiheeseen. Menetelmää käytetään paljon, koska se on suhteellisen helppo toteuttaa ja oikein toteutettuna se on tehokas ja innostava menetelmä. (Partridge 2015; Prewitt 2011; Brown & Isaacs 2001.)

Learning Cafe toteutetaan jäljittelemällä kahvilamaista rentoa tunnelmaa. Pieni joukko, 4¬‒5 osallistujaa, kokoontuu ikään kuin kahvilapöytään keskustelemaan heille annetusta aiheesta sovituksi ajaksi, jonka jälkeen he siirtyvät toiseen kahvilapöytään osallistumaan uuteen keskusteluun. Eri kahvilapöytiä ja niissä keskusteluja on yleensä 3¬‒5 ja yhteen pöytäkeskusteluun on hyvä varata aikaa noin 20‒30 minuuttia. Keskustelussa oleellista on kuunnella kaikkien osallistujien mielipiteitä ja ajatuksia tyrmäämättä niitä ja näin tuoda esille uusia näkökulmia, ei niinkään ratkoa erilaisia ongelmia. Työskentelyn on tarkoitus olla mahdollisimman luovaa ja uutta ajattelua tuottavaa. Jokaisessa kahvilapöydässä on isäntä/emäntä vetämässä keskustelua. Hänen tehtävänään on kertoa pöytään tulevalle ryhmälle keskustelun teema ja lyhyesti orientoida mistä edelliset ryhmät ovat jo keskustelleet. Keskeistä on, että isäntä/emäntä innostaa aina uutta ryhmää keskustelemaan ja tuottamaan uusia ajatuksia annettuun aiheeseen. Kaikki esille nousseet ajatukset kirjataan ylös, tyypillisesti fläppipaperille. Keskustelun ilmapiirin on tarkoitus olla mahdollisimman avoin ja vapaa kuten kahvipöytäkeskusteluissa yleensäkin. Mukavan rento ympäristö edistää keskustelua ja siksi myös siihen kannattaa kiinnittää huomiota. Kun kaikki kierrokset kahvilapöydissä on tehty niin pöydän isäntä/emäntä tekee yhteenvedon käydyistä keskusteluista. (Partridge 2015; Haukijärvi ym. 2014; Prewitt 2011; Brown & Isaacs 2001.)

Learning Cafe toteutukset tapahtuvat yleensä fyysisessä tilassa, esimerkiksi luokassa, mutta yhtä hyvin Learning Cafen voi toteuttaa virtuaalisessa ympäristössä verkossa, jossa ollaan reaaliaikaisesti yhdessä tuottamassa käsiteltävään asiaan erilaisia näkökulmia. Oppimisen näkökulmasta mahdollisimman vuorovaikutteiset ja monipuoliset verkkototeutukset herättävät kiinnostusta ja ovat motivoivia (Chang & Kang 2016). Hyvän verkkokokonaisuuden rakentaminen on haastavaa ja vaatii opettajalta hyvää verkkopedagogista osaamista. Opettajalla tulee olla käytettävissään joustava sähköinen oppimisympäristö, johon on mahdollista rakentaa vuorovaikutteisia elementtejä, jolloin esimerkiksi Learning Cafen tyyppiset reaaliaikaiset ryhmätyöskentelyt tulevat mahdollisiksi.

Oppimisteoriat ovat ajalta ennen verkko-oppimista. Behavioristinen näkemys painottaa aineiston merkitystä, kognitiivinen oppimisen prosesseja ja konstruktivistinen näkemys oppijan omaa roolia tiedon rakentajana. Uudeksi digiajan oppimisteoriaksi on nousemassa konnektivismi, joka korostaa oppimista sosiaalisissa verkostoissa. (Ally 2008.) Konnektivismin mukaan oppimishaluisen tulisi kytkeytyä oppimisverkostoihin ja olla vuorovaikutuksessa verkoston ihmisten ja tiedon kanssa. (Siemens 2005.) Tulevaisuudessa opettajan keskeisinä tehtävinä saattaa yhä enenevässä määrin olla oppimisverkostojen luonti tietyn aihepiirin ympärille sekä oppimishalun herättäminen opiskelijoissa. Learning Cafe työskentelyn toteuttaminen verkossa on hyvä esimerkki menetelmästä, jossa voidaan kerätä eri alojen edustajia pohtimaan samaa aihepiiriä ja innovoimaan yhdessä ratkaisuja asetettuihin ongelmiin tai kysymyksiin.

Digitaalisen Learning Cafen toteutus

Digitaalinen Learning Cafe toteutettiin kesäkuussa 2017 osana Digitaaliset palvelut arjen apuna verkko-opintojaksoa. Learning Cafe -menetelmä sopii hyvin toteutettavaksi verkkoympäristössä. Sen toteutus vaatii hyvää etukäteissuunnittelua ja selkeät sekä mahdollisimman yksityiskohtaiset toimintaohjeet opiskelijoille ennen reaaliaikaista Learning Cafe tapahtumaa.

Digitaalinen Learning Cafe toteutettiin hyödyntäen Moodle-oppimisympäristöä, Adobe Connect verkkokokousjärjestelmää (AC) sekä Padlet-seinää. Moodleen koottiin seikkaperäiset ohjeet Learning Cafen toteuttamisesta tarkkoine aikatauluineen ja linkkeineen työskentelyssä hyödynnettäviin kohteisiin. AC:n opettajan tila toimi yhteisenä kokoontumistilana sekä alustuksessa että yhteenvedossa, ja kunkin ryhmän isännän tai emännän AC-tila kahvilaympäristönä, jossa keskustelua käytiin ryhmän aihepiirin ympärillä. Padlet toimi alustana keskusteluissa nousseiden ajatusten kirjaamiseen, vastaavasti kuin fläppipaperi perinteisessä Learning cafeessa. Lisäksi sitä hyödynnettiin keskusteluiden alustuksessa tekstin, kuvien ja videoiden muodossa.

Opintojaksolle osallistuvat opiskelijat jaettiin pienryhmiin (3 osallistujaa/ryhmä). Ryhmä valmisteli Padlet-seinälle Learning Cafe ’pöydän’, jonka tavoitteena oli pohjustaa keskustelua, olla houkutteleva ja mahdollisimman innostava yhteiseen keskusteluun. Kukin ryhmä valitsi keskuudestaan isännän tai emännän, jonka tehtävänä oli fasilitoida Learning cafe -keskustelua ryhmän AC-tilassa Padlet-seinää hyödyntäen.

Ennen Learning Cafen aloittamista osallistujien tuli testata ohjelmisto-, laite- ja verkkoyhteensopivuus laitteelta, josta aikoo sessioon osallistua. Opiskelijoita pyydettiin testaamaan erityisesti äänen kuuluvuus. Testauksesta tulee olla opiskelijoille selkeä ohje verkko-oppimisympäristössä esimerkiksi videon avulla. Oppimissessio, jolla Learning Cafe toteutettiin, aloitettiin kokoontumalla opettajan AC-tilaan, jossa käytiin Moodle-alustalla oleva aikataulu yhdessä läpi ja varmistettiin, että kukin tietää, minkä ryhmän AC-tilassa (digitaalisessa Learning Cafe -pöydässä) kulloinkin tuli olla. Opettajan AC-tila ja opintojakson Moodle-alusta olivat koko ajan opiskelijoiden käytössä siltä varalta, että opiskelija eksyi ryhmästään siirtyessään ryhmien AC-tiloista toisiin.

Varsinainen Learning Cafe aloitettiin siirtymällä sovittuun kellonaikaan kunkin ryhmän ensimmäiseen digitaaliseen Learning Cafe -pöytään. Linkit kaikkiin näihin AC-tiloihin oli koottu Moodle-alustalle. Korkeakouluopiskelijat kirjautuivat huoneisiin omilla AD-tunnuksillaan, korkeakoulujen yhteisen Haka-kirjautumisen kautta. Learning Cafe isännän/emännän oli hyvä pyytää osallistujilta ääninäyte, kun he olivat kirjautuneet keskusteluun. Koska AC-työskentely oli opiskelijoille entuudestaan tuttua, oli heitä jo aiemmin ohjeistettu (ja ohjeet Moodle-alustalla), mitkä ovat tavallisimmat ongelmatilanteet AC-ympäristössä ja mitä niiden korjaamiseksi voi tehdä. Näin heillä oli osaamista reagoida esimerkiksi toimimattomaan ääniyhteyteen.

Kun Learning Cafen osallistujat olivat kaikki paikalla, isäntä tai emäntä alusti keskusteltavan aiheen hyödyntäen ryhmän Padletille kokoamaa aineistoa. Tämä jälkeen aloitettiin yhteinen keskustelu, jonka lisäksi osallistujien oli mahdollista kirjoittaa kommentteja keskusteltavasta aiheesta Padlet-seinälle ja näin rakentaa yhteistä tiedon kokonaisuutta. Keskusteluun varatun ajan jälkeen osallistunut ryhmä siirtyi seuraavaan digitaaliseen Learning Cafe -pöytään. Tieto siirtymisen ajankohdasta sekä linkki seuraavaan AC-tilaan oli aina saatavilla Moodle-alustan lisäksi kussakin AC-tilassa. Näin siirtymiset tapahtuivat mahdollisimman jouhevasti. Tarkka aikataulutus on oleellista vaihtojen sujuvuuden kannalta. Kun kukin ryhmä oli kiertänyt kaikki keskustelut, opiskelijat palasivat opettajan AC-tilaan keskustelujen yhteenvetoja varten. Learning cafeen toteutuksen aikana opettaja siirtyi keskustelutiloista toiseen seuraamassa opiskelijoiden keskustelua, aivan kuten fyysisessä tilassakin.

Toteutetun Learning Cafen palautekysely

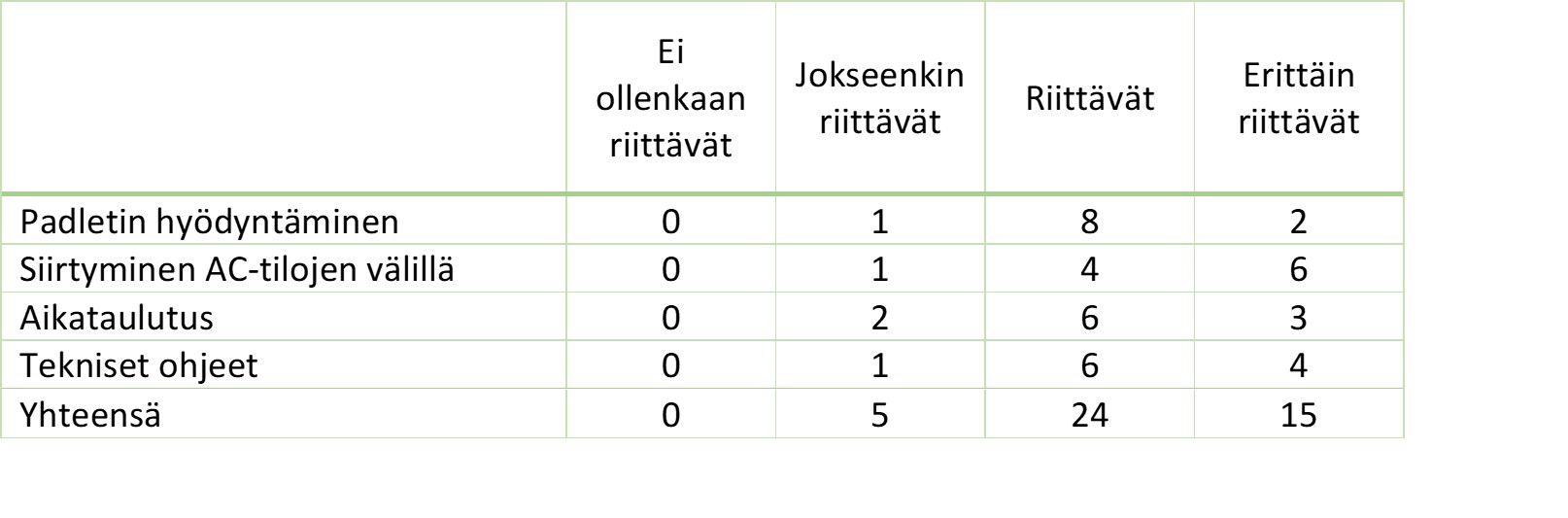

Opintojaksolle osallistui 14 opiskelijaa kolmesta eri ammattikorkeakoulusta, jotka vastasivat sähköiseen Webrobol-kyselyyn opintojakson päätyttyä. Vastauksia saatiin 11 opiskelijalta. Vastaajista suurin osa oli liiketalouden alalta (5). Sekä tietojenkäsittelyn alalta että tieto- ja viestintätekniikasta oli kaksi vastaajaa. Lisäksi tekniikan alalta sekä palveluliiketoiminnasta oli kummastakin yksi vastaaja. Osa opiskelijoista hallitsi tietotekniikkaa ja käsiteltävää aihetta erittäin hyvin, osalle käsiteltävä aihe ja verkkoympäristössä toimiminen oli heikommin hallussa. Kukaan opiskelijoista ei ollut osallistunut aiemmin digitaaliseen Learning Cafe -toteutukseen, myös luokassa toteutettu Learning Cafe oli lähes kaikille vieras.

Palautekyselyssä oli kolme teemaa ja niihin liittyvät väittämät olivat:

1. Digitaalinen Learning Cafen teknisen toteutuksen toimivuus: padlet; reaaliaikaisuus, yhteyksien toimivuus; äänien toimivuus; esitysten näkyminen

2. Digitaalinen Learning Cafe ohjeistusten riittävyys: tekniset ohjeet; liikkuminen huoneissa; aikataulutus

3. Digitaalinen Learning Cafe oppimiskokemuksena: suosittelisitko digitaalista Learning

Cafeta muille opintojaksoille; digitaalinen Learning Cafe oli positiivinen kokemus ja miksi; mitä kehittäisit

Jokaiseen teemaan liittyi myös avoin kysymys, jolla saatiin täydentäviä vastauksia kysyttyihin sisältöihin liittyen. Vaikka vastaajien määrä oli pieni, antoivat he paljon hyvää tietoa toimivuuteen liittyvissä avoimissa vastauksissa.

Opiskelijoiden kokemukset digitaalisen Learning Cafen toteutuksesta

Digitaalinen Learning Cafen teknisen toteutuksen toimivuus

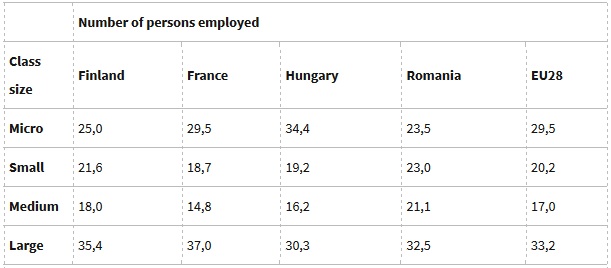

Ensimmäisessä teemassa haettiin palautetta Learning Cafen teknisen toteutuksen toimivuudesta, joka sisälsi neljä toimivuusaluetta. Suurin osa vastaajista piti Padletien ja opiskelijoiden omien AC-tilojen teknistä toteutusta pääasiassa toimivana. Sen sijaan yhteyksien ja äänien toimivuutta pidettiin vain jokseenkin toimivina (taulukko 1).

Taulukko 1. Digitaalisen Learning Cafen tekninen toimivuus Moodle oppimisympäristössä.

Neljä opiskelijaa oli vastannut avoimeen kysymykseen ja täydentänyt palautetietoa teknisen toimivuuden osalta. Kolme kommenteista liittyi äänien kuuluvuuteen, lisäksi kaksi kommenttia liittyi materiaalien jakamiseen Learning Cafe -tilassa. Äänien osalta kommentit liittyivät äänien särisemiseen, häviämiseen ja äänien vain osittaiseen kuulumiseen.

”Kaikilla pitäisi olla hyvät mikrofonit ja kuulokkeet. Usein törmää siihen, että aina joitain ei kuule hyvin tai äänet särisevät.”

”Learning Cafeen osallistuvien tulisi ehdottomasti tarkistaa, että kuulokkeet/mikrofonit toimivat. On kurja kuunnella esitystä, kuin vain osan sanoista kuulee.”

”AC huoneessamme oli kaksi ”share my screen” ikkunaa auki ja materiaalit näkyivät kahteen kertaan jaettavalle yleisölle. Emme saaneet päällekkäisiä ikkunoista toista suljettua ollenkaan syystä tai toisesta. Liekö oikeuksiin liittyvää kun toinen oli host ja toinen presenter vaiko vain jokin ”ominaisuus”.”

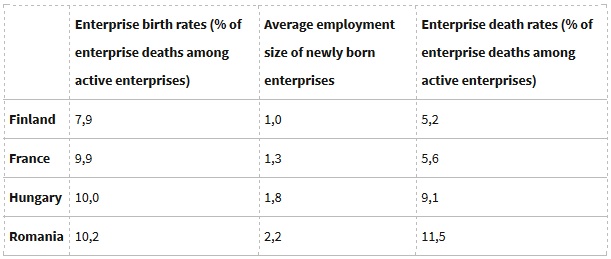

Digitaalinen Learning Cafe ohjeistusten riittävyys

Suurin osa vastaajista koki, että Learning Cafen toteutukseen liittyvät ohjeet olivat riittävät tai erittäin riittävät. Etenkin ohjeistus joka liittyi liikkumiseen AC-tilojen välillä, koettiin erittäin riittäväksi. Myös Padletien hyödyntäminen, aikataulutus ja tekniset ohjeet olivat vastaajien mielestä pääosin riittävästi ohjeistettu (taulukko 2).

Taulukko 2 Digitaalinen Learning Cafe ohjeistusten riittävyys (n=11).

Avoimissa vastauksissa (3 kappaletta) tuotiin esille aikataulutukseen liittyviä ehdotuksia, yksi kommentti liittyi toiveeseen saada lisää tukea Padletin käyttöön.

”Ohjeet olivat hyvät. Jotta saataisiin enemmän keskustelua aikaiseksi, voisi aikaa per huone olla hieman enemmän.”

”Padletin ohjeistukseen olisin kaivannut jotain tukea – koko ryhmä oli uusia padlet käyttäjiä ja kun loimme uusia tarroja niin toisen oikeudet liikutella tarroja/lappuja ei onnistunut. Mutta selvisimme että ei paniikkia.”

Digitaalinen Learning Cafe oppimiskokemuksena

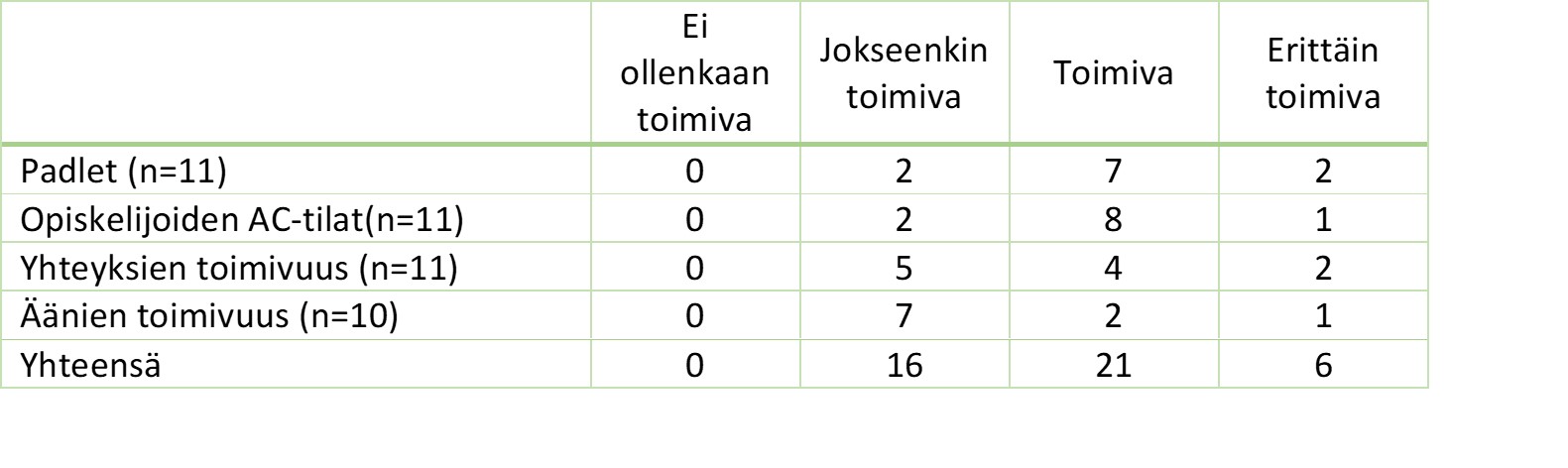

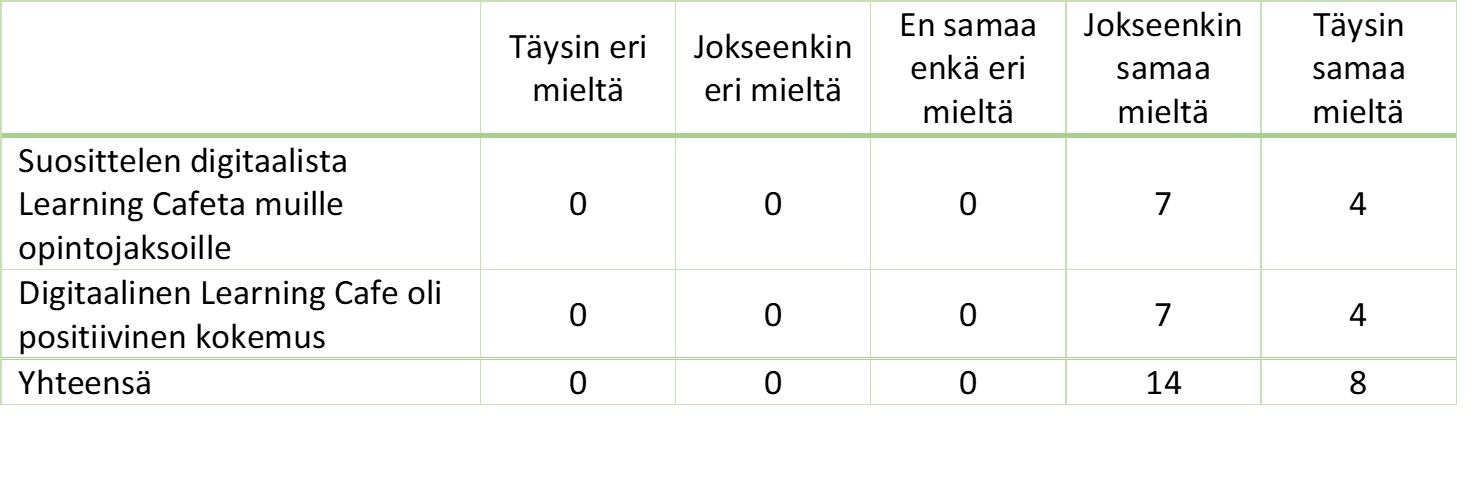

Vastanneet opiskelijat kokivat Learning Cafen positiivisena oppimiskokemuksena ja olivat valmiita suosittelemaan sitä muillekin opintojaksoille (taulukko 3).

Taulukko 3. Digitaalinen Learning Cafe oppimiskokemuksena (n=11)

Avoimessa kysymyksessä opiskelijoilta kysyttiin mikä vaikutti heidän oppimiskokemukseen verkossa toteutetusta Learning Cafesta. Lähes kaikki kommentit toivat esille positiivisia kokemuksia, vain yhdessä kommentissa tuotiin esille yhteysongelmat.

”Mielenkiintoinen, liian vähän käytetty tapa oppia.”

”Nettiyhteyksien tuomat vaikeudet.”

”Mielenkiintoiset aiheet, hyvät ohjeet, hyvät esitykset sekä oma halua oppia digitaalinen Learning Cafe.”

”Liikkuminen huoneesta toiseen oli saumatonta kunhan linkit on kunnossa.

Hienosti sai palautetta ja kysymyksiä live esityksen jälkeen mikä oli sekä hämmentävää ja mukavaa. Oli hienoa keskustella kanssaopiskelijoiden ja opettajien kanssa.”

”Opiskelisin useampia kursseja mieluusti Learning Cafen kautta. Mahtava kokemus! Kiitos!”

Opiskelijat (5 kappaletta) toivat esille myös joitakin huomioitavia kehittämisehdotuksia digitaalisen Learning Cafeen toteutukseen.

”Ehkä se, että jokaisella ryhmällä olisi silti esim. powerpoint asiastaan jonka voi myös laittaa Padlettiin luettavaksi tai muuten esittelyn osana. Välillä näitä pelkkiä muistilappuja on vähän tylsä lukea.”

”Hyvin joustava ja hyvin toimiessaan toimiva oppimisympäristö. Yhteysvaatimukset voisi olla jossakin olemassa. Välttämättä puhelimesta jaettu netti ei riitä, jos verkko on heikko.”

”Learning Cafen AC:n sekä Padletin yleisiä ”vikatilanteita” FAQ uusille käyttäjille koska alkubriiffissä ei välttämättä osaa vikatilantesta mitään kysyä.”

Pohdinta

Kokonaisuudessaan opiskelijat antoivat positiivista palautetta verkossa toteutetusta Learning Cafesta. Opiskelijat kokivat, että tekninen toteutus oli toimiva ja että ohjeistukset olivat pääosin riittävät, ja he olivat valmiita suosittelemaan Learning Cafe toteutusta myös muille opintojaksoille. Tässä palautekyselyssä keskityttiin Learning Cafen tekniseen toteutukseen ja toteutuksen vaatimiin ohjeisiin, jotka ovat oleellisia edellytyksiä onnistuneeseen, oppimista tukevaan yhteistoiminnalliseen työskentelyyn verkossa. Yhteistoiminnallisen työskentelyn tavat ovat oppimisen näkökulmasta tehokkaampia kuin yksilötyöskentelyyn perustuvat työskentelymenetelmät, myös verkkoympäristössä (MacNeill et al 2014; Vuopala ym. 2016), joten tärkeää on pyrkiä rakentamaan toteutuksia, jotka mahdollistavat yhteisen ryhmätoiminnan ja tiedonrakentamisen verkossa.

Yhteistoiminnallinen työskentely verkossa voi olla reaaliaikaista tai eriaikaista. Työkaluja eri työskentelymuotoja varten on paljon erilaisia. Reaaliaikainen verkkoviestintä voi olla tekstiin, ääneen ja liikkuvaan kuvaan pohjautuvaa. Tekstipohjaisia pikaviestimiä, kuten Chat-työkalua voi usein hyödyntää reaaliaikaisen keskusteluyhteyden, esimerkiksi opintojaksolla käytetyn AC- verkkokokousjärjestelmän lisänä. (Sore, Meriläinen & Kivilahti 2011.) Eriaikaisia yhteistoiminnallisia työskentelymuotoja verkkoympäristössä ovat esimerkiksi yhteisen aineiston tuottaminen wikillä, blogi-kirjoittaminen tai keskustelupalstat, joissa käytetään vastaustoimintoa. (Vuopala ym. 2016; Sore ym. 2011.) Ward ym. (2010) selvittivät opettajien ja opiskelijoiden käsityksiä verkko-opiskelun laadusta, ja etenkin opiskelijat kokivat reaaliaikaisen työskentelyn verkossa yhtä hyväksi kuin kasvokkain tapahtuvan luokkaopetuksen ja olivat valmiita valitsemaan myös muita opintoja sen mukaan, että toteutuksessa käytettäisiin reaaliaikaisia verkko-opiskelun tapoja. Tulos vastaa myös tämän artikkelin palautekyselystä saatuja mielipiteitä.

Lähteet

Ally, M. 2008. Foundations of educational theory for online learning. [Verkkodokumentti]. Teoksessa Anderson, T. (ed.) The theory and practice of online learning. Second edition. Edmonton: AU Press. 15-44. [Viitattu 12.10.2017]. Saatavissa: http://biblioteca.ucv.cl/site/colecciones/manuales_u/99Z_Anderson_2008-Theory_and_Practice_of_Online_Learning.pdf

Brown, J. & Isaacs, D. 2001. The World Cafe: Living knowledge through conversations that matter. The Systems Thinker. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 12(5), 1–5. [Viitattu 15.10.2017]. Saatavissa: http://www.theworldcafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/STCoverStory.pdf

Chang, B. & Kang, H. 2016. Challenges facing group work online. Distance Education. [Verkkodokumentti]. Vol. 37(1), 73-88. [Viitattu 15.10.2017]. Saatavissa: https://doi.org/10.1080/01587016.1154781

Haukijärvi N., Kangas A., Knuutila H., Leino-Richert E. & Teirasvuo N. 2014. Tavoitteena aktiivinen ja työelämälähtöinen oppiminen. [Verkkodokumentti]. Turun ammattikorkeakoulun oppimateriaaleja 91. Turun ammattikorkeakoulu. [Viitattu 10.11.2017]. Saatavissa: http://julkaisut.turkuamk.fi/isbn9789522165107.pdf

MacNeill, H., Telner, D., Sparaggis‐Agaliotis, A. & Hanna, E. 2014. All for one and one for all: Understanding health professionals’ experience in individual versus collaborative online learning. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 34(2), 102-111. [Viitattu 10.11.2017]. Saatavissa: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/chp.21226/full

Prewitt, V. 2011. Working in the cafè: lessons in group dialogue. The Learning Organization. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 18(3), 189-202. [Viitattu 15.10.2017]. Saatavissa: https://doi.org/10.1108/09696471111123252

Partridge, M. 2015. Evaluation Café – A review of literature concerning World Cafe methodology used as an evaluative tool in education. Innovative Practice in Higher Education. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 2(2). [Viitattu 17.10.2017]. Saatavissa: http://journals.staffs.ac.uk/index.php/ipihe/article/viewFile/76/154

Siemens, G. 2005. Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International journal of instructional technology and distance learning. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 2(1), 3-10. [Viitattu 14.10.2017]. Saatavissa: http://itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Sore, S., Meriläinen, J. & Kivilahti, R. 2011. Yhteistyöskentelyn uudet muodot. Teoksessa: Haasio A. & Salo K. (toim.) AMK 2.0: Puheenvuoroja sosiaalisesta mediasta ammattikorkeakouluissa. [Verkkodokumentti]. Seinäjoen ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja B. Raportteja ja selvityksiä 51. 116-133. [Viitattu 12.10.2017]. Saatavissa: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/32091/B51.pdf

Vuopala E., Hyvönen P. & Järvelä S. 2016. Interaction forms in successful collaborative learning in virtual learning environments. Active Learning in Higher Education. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 17(1), 25-38. [Viitattu 2.11.2017]. Saatavissa: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1469787415616730

Ward M.E., Peters G. & Shelley K. 2010. Student and Faculty Perceptions of the Quality of Online Learning Experiences. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. [Verkkolehti]. Vol. 11(3), 57-77. [Viitattu 4.11.2017]. Saatavissa: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/867/1610

Kirjoittajat

Hannele Tiittanen työskentelee yliopettajana Lahden ammattikorkeakoulussa sosiaali- ja terveysalalla.

Sariseelia Sore työskentelee lehtorina Lahden ammattikorkeakoulussa liiketalouden ja matkailun alalla.

Artikkelikuva: https://www.pexels.com/photo/working-typing-macbook-computer-7350/ (CC0)

Julkaistu 28.2.2018

Viittausohje

Tiittanen, H. & Sore, S. 2018. Learning Cafen toteutus verkko-opinnoissa. LAMK RDI Journal. [Verkkolehti]. [Viitattu pvm]. Saatavissa: http://www.lamkpub.fi/2018/02/28/learning-cafen-toteutus-verkko-opinnoissa/

![]()