Growing a business and operating sustainably in an ever-competitive landscape is a challenge well known to micro business owners and entrepreneurs in any business sector. Within the spectrum of alternative local food systems (LFS) challenges and opportunities are unique. The Baltic Sea Food project was initiated to investigate these LFS, build and pilot business models for them, and simultaneously promote awareness of local food in the Baltic Sea Region (BSR). The following article presents the research project and takes a look at the feasibility of implementing the recommendations.

Authors: Lydia Rusanen & Brett Fifield

Baltic Sea Food Project

The EU and Interreg funded Baltic Sea Food Project was initiated with the aim to optimize the B2B performance of local producers within the Baltic Sea Region (BSR). The action points included, undertaking in-depth research across ten countries, formulating workable business models from the findings, piloting the business models, and promoting awareness of local food through workshops and promotion of business opportunities to networks and other local food representatives. (Interreg Baltic Sea Region 2017.) The thesis upon which this article is based, deals with work package two of four, undertaking the research stage of the project (Rusanen 2019).

Local Food Systems: Development opportunities

Local food systems (LFS) are alternatives to the mainstream, high yield focused, food systems, that in recent years have come under criticism for their unsustainable methods, negative environment and social impacts, and lack of support for local economies. LFS can be defined in a number of ways. According to most consumers, LFS are understood to be providers of food grown using sustainable and often organic methods, within a close geographical proximity to where it is sold. Additionally, they should support the local community, building close relationship between producers and consumers. (Roy 2006, 9-12.)

Producers within LFS face unique challenges exacerbated by their lack of business knowledge and financial resources. These challenges include connecting with B2B buyers and building mutually beneficial relationships with them, finding economical distribution channels that can meet the needs of B2B customers, and complying with the stringent and continually evolving regulations. Regulatory control extends to all areas of the business, in particular, labelling of products, food hygiene safety, and transportation requirements. These challenges represent significant opportunities for growth.

A fundamental part of value chain in LFS is the origin of the food, the story behind it is the intrinsic value. This justifies the comparably higher price of local foods. Blockchain is an emerging technology that optimizes this. It is a decentralized, chronologically recorded chain of transactions, a secure system that promises to replace the middlemen in multiple business situations. Blockchain is already being used in food systems for optimizing delivery routes, whilst sending real time location updates to buyers and sellers. It also replacing the costly and time-consuming certification processes for proof of origin, organic labels and food hygiene. Additionally, instant tracking of source in cases of outbreaks is realised. (Crawford 2018.)

Research methods

The research was implemented using a multiple case study strategy with data collection taking the form of surveys for quantitative data and focus groups and interviews for qualitative data. Stakeholders across all ten countries were included in the research.

The first phase of data collection comprised of two versions of an electronic survey, one for completion by the distributors and the other by the networks. The surveys themselves were translated into the ten local languages and made available on the webropol service. In the second phase of data collection, stakeholders took part in semi structured interviews or focus groups, covering five key themes; pricing, distribution, communication, ordering, and future challenges.

The Business Model Canvas by Osterwalder & Pigneur (Osterwalder 2004) ) was used to bring the results together and develop a scalable business model that would be piloted in the ten countries.

Research Findings

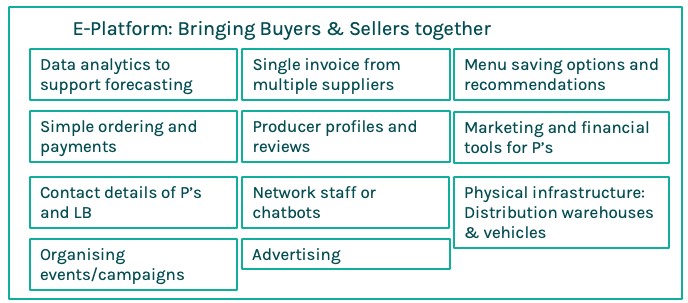

The research unearthed a vast amount of information, from which business models could be drawn up, implemented, and finally tested. The outcome of the research thesis itself was a hybrid BMC aimed towards producers within the BSF (Rusanen 2019, 77). As producers become more integrated and grow within the local food networks, they can turn to the BMC to gain a better understanding of the factors that should be considered as they grow. An interesting and important recommendation that effects all parts of the business model is that of building an e-platform upon blockchain technology. The question that arises at this point is, how feasible is the integration of this technology system into existing e-platforms.

The research indicated that many forms of e-platforms are being used throughout the BSR. These platforms vary in the way they have been implemented and used, some are government run platforms, others are privately run, for profit businesses. Not all platforms are used for ordering and payments. The key element is that the platforms are region wide, in other words they allow access to all LFS stakeholders within the local region.

Moving forward to implementation

Ultimately, the study answered the research questions and additionally presented a recommended best-case scenario situation for LFS. In theory, implementing the recommendations promises great gains for all members of the value chain. However, in practice, making such changes to existing systems is less than straightforward. The producers who are at the core of this change, typically face barriers such as time constraints, lack of business knowledge, and lack of financial resources. Some LFS whose capacity is too small to warrant expansion might also resist implementation of the recommendations. It is clear that support is needed from government sources in order to ensure producers are receiving sound business advice along with tools for pricing and marketing their products.

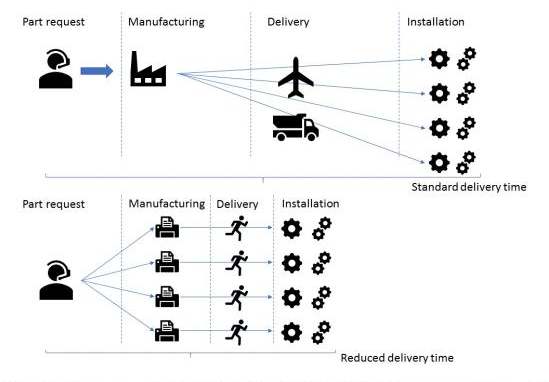

Figure 1. Best-case scenario (Figure by Lydia Rusanen)

The best-case scenario shown in image 1 was based on an e-platform run using blockchain technology, however, EU funding is needed to initiate its use and help producers and distributors make the changes to their existing practices so that they can fit in to the blockchain system.

There is a real risk that the recommendations made will not be implemented if this ground work is not laid. If sustainability and security is sought after by EU policy, it might be necessary to consider incentives for local stakeholders to follow this route. Especially if the initial investment is a trade-off with profit.

Undeniably sustainability and blockchain are two trends that promise to take the business world by storm in the coming decade. LFS are part of a growing environmental movement and rather than focus on well known, age-old systems, the way needs to be paved for smarter technology.

References

Crawford, E. 2018. From 7 Days to 2 Seconds: Blockchain Can Help Speed Trace-back, Improve Food Safety and Reduce Waste. [Cited 13 Nov 2018] . Available at: https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2018/11/06/From-7-days-to-2-seconds-Blockchain-can-help-speed-trace-back-improve-food-safety-reduce-waste

Interreg Baltic Sea Region. 2017. Baltic Sea Food Application Form.

Osterwalder, A. 2004. The Business Model Ontology: A Proposition In A Design Science Approach. PHD Thesis. Universite de Lausanne. [Cited 13 Nov 2018]. Available at: http://ip1.sg/pub/BMcanvas/2004-Osterwalder_PhD_BM_Ontology.pdf

Roy, H. 2016. The Role of Local Food in Restaurants: A Comparison Between Restaurants and Chefs in Vancouver, Canada and Christchurch, New Zealand. PHD Thesis. University of Canterbury. Christchurch. [Cited 23 Oct 2018]. Available at: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/12694

Rusanen, L. 2019. Sustainable B2B Business Models for Local Food in The Baltic Sea Region. Bachelor’s Thesis. Lahti University of Applied Sciences. Lahti. [Cited 16 May 2019]. Available at: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-201905027326

Authors

Lydia Rusanen has studied Business and Administration at The Faculty of Business and Hospitality Management at Lahti University of Applied Sciences and has graduated and received a BBA degree in May 2019.

Brett Fifield has been actively involved in developing Business Schools for the Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences since 1994. Most recently he has been responsible for courses in Futures and Strategies, Innovation and Creativity, Digital Services and Leadership and Management of Projects in Distributed Organizations in Lahti University of Applied Sciences.

Illustration: https://pxhere.com/fi/photo/810606 (CC0)

Published 9.9.2019

Reference to this publication

Rusanen, L. & Fifield, B. 2019. A comprehensive investigation of local food systems in the Baltic Sea Region. LAMK Pro. [Cited and date of citation]. Available at: http://www.lamkpub.fi/2019/09/09/a-comprehensive-investigation-of-local-food-systems-in-the-baltic-sea-region/